Leadership in its rawest form is the ability to lead individuals to achieve a goal set by the leader or a common goal of the organisation(s). Alexander the Great once said, “I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a lion”. This in itself lends to the idea that he had a set view of how a leader should act. Although this idea of a ‘lion’ leads to the view that a leader must be strong, powerful, and organised, yet leadership can come in many forms. Even in the days of Alexander the Great, leaders are at the forefront of the organisation and will ultimately take accountability for the failure or success of the organisation’s efforts. This means that leaders have to be knowledgeable in their field and be able to support, nurture and positively enable their team to achieve a common goal or the goal of the organisation (Maeda & Bermont, 2011). Despite there being many theories of what a leader ‘looks’ like (these will be discussed further in the essay), the fundamentals of leadership are still the same, which according to Rhode (2012) and Stanik-Hutt (2008) is to inspire and influence their followers.

Throughout history, leadership has changed and developed with how we view the needs of society and the individuals within an organisation. Northouse (2013) outlines the move from leadership is about power and domination in the early 1900s to the 21st century where leaders are now expected to influence others, whether that be by trust or enhancing individual development to achieve a set outcome. Two theories that perpetuate the idea of power and domination come from the idea that either they are born to be a leader (Great Man) or that they have the traits that will enable them to be or become great leaders (trait theory) (Organ, 1996; Zaccaro, 2007). Organ (1996) chose to revisit the idea that some people simply ‘have’ it or they ‘don’t’ (The great man theory) because a doctoral candidate chose to speak about leadership with a contradictory view, stating “most of you simply don’t have it”. Although this theory enables us to think about some of the great leaders in history being born from royalty or from other great leaders, this theory does not take into consideration that leaders may come about due to their environment (contingency theory) (Fielder, 1964) or the relationships built within their organisations (relationship theory) (Weymes, 2002).

Despite society having some set ideas of how a leader should be, individual conceptions of how a leader should be or act like are at the discretion of the individual (Hunt, 2004). The problem in trying to define leadership is that many different ideas have developed and a leader that works in one organisation may not work in another.

As outlined previously, leadership styles can be influenced by both the style of the organisation and the employees. As leaders are now having to be more aware of the development of the organisation and the individuals within the organisation, what may be seen as effective leadership a few decades ago may be different from what we expect of leaders in the 21st century. As society has changed from a hierarchical class system where you ‘know your place’, to everyone is now given the opportunity to develop themselves and to have a more inclusive and dynamic workplace this has changed the view of what an effective leader is. A good example is factories, which we more prevalent in the early 1900s, which are based around a machine model of organisation (Morgan, 1986) and focused more on the production of the products rather than the development of professionalism and leadership. As there are now a vast number of different styles of organisations, the focus has shifted from merely producing end products to now having culture development and implementation of furthering individual training in both leadership and skills needed for the specific job roles.

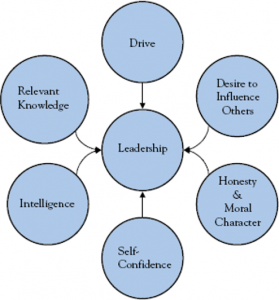

The above image outlines some of the characteristics that make an effective leader but finding an individual who has managed to develop each of these would be difficult. Thus, bringing back the idea that it may be the organisation(s) goals and style that influences a particular leader.

Take for instance a prison, this volatile and fast-paced workplace that may require a leader who is effective at maintaining control and order such as an autocratic leader who is ‘the boss’ and holds authority over their subordinates. Although this style of leadership may work in this workplace, Van Vugt, Jepson, Hart & De Cremer (2004) found that followers of autocratic leaders tended to leave and take their resources elsewhere. Conversely to autocratic leadership, a democratic leader allows followers to have a voice and empowers them to make decisions (Gastil 1994). Bhatti, Maitio, Shaikh, Hashmi & Shaikh (2004) found that teachers who were able to work in a ‘free’ atmosphere and were able to share their views with their leaders in a positive environment were more satisfied with their job. This amplifies the idea that leaders who enable their followers to take ownership of their creativity, is essential to maintaining effective leadership.

Another key measure of effective leadership noted by Palmer, Walls, Burgees & Stough (2001) is the level of emotional intelligence that one has. Although Palmer et al. (2001) struggled to find research promoting the idea that emotional intelligence is linked to effective leadership, he suggests that this type of intelligence is closely linked to transformational leadership (promoting leadership by responding to individual needs of their followers (Bass & Riggio, 2006). This kind of leadership has been related to increasing team communication, cohesion and conflict management, individual and team development; intellectual stimulation, and consideration (Dionne, Yammarino, Atwater & Spangler 2004; Dvir, Eden, Avolio & Shamir 2002; Murphy, 2005). On the other hand, the transactional style of leadership is based on the idea that rewards will be given to those that perform well and ‘punished’ if they don’t (Northouse, 2013). Although this style of leadership aims to promote the overall progress of the goal of the leader or organisation, it does not take into consideration the individual needs of the followers.

To have the characteristics of a leader does not simply qualify someone to be a ‘good’ leader, but rather the context of the workplace and the needs of the followers. Thus, defining specific characteristics can be tricky. Drawing back to the idea that some leaders are born leaders, and some are born with traits needed to become great leaders, not everyone has this advantage and thus must develop themselves to become a leader or look to their organisation for this development.

For one’s development in leadership, you must first and foremost understand your strengths and weaknesses. Being able to identify the areas you need further development in will ultimately enable you to develop quickly as a leader, it also builds on the ability to reflect on your practises and skills. Tourish (2012) and Johnson & Bechler (1998) outlines the importance of being an excellent reflective practitioner as it enables you to learn from the mistakes you have made and better prepares you for areas that need to be actively developed. Being a reflective practitioner is an attribute of a teacher that is regarded to be one of the most important (Larrivee, 2000). An organisation must also allow for reflection to take place and provide constructive feedback to guide their employees to develop in their critical areas first. For employees who are interested in becoming leaders, an organisation must provide training in the skills needed to become an effective leader while also promoting the idea that everyone has the potential to become leaders. This style of leadership development is known as positive organisational scholarship (POS) and emphasizes the strengths and capabilities of those within the organisation (Ashford & DeRue, 2012). So, by first identifying the areas with which you are most influential, may give you a platform for allowing your organisation to develop you as a leader in specific areas. This comes in the form of a SWOT analysis, which will be discussed later in the essay.

Stanik-Hutt (2008) gives two ways in which an individual and an organisation can develop effective leadership together.

- Building relations – Being able to build relationships within the organisation gives a real platform in enabling leadership. Participative theory (democratic leadership) suggests that these types of leaders encourage their followers to contribute in the design of their ideas by distributing responsibility, empowering their followers and helping followers to govern themselves (Gastil 1994; Woods, 2005). By building trust with individuals and having positive relationships, they will be more willing to work harder and more effective. Although having good relations can have an overall positive impact on leadership, if those relationships do become fraught then leadership can become hindered by those who may want to sabotage the goal of the leader, so maintenance of positive relationships is vital.

- Teamwork – Teamwork lends itself to the idea that being able to work well in a team, may mean that you have some of the qualities needed to become a leader. Although teamwork in itself does not indicate how good of a leader you are, it does indicate as to how adaptable you can be to other ideas and how well you listen to others. For those in larger organisations such as a school, different types of leaders can work collegially to achieve the set goals of the organisation (Northouse, 2013).

Listening is another crucial skill in being able to develop yourself as a leader and for an organisation to develop others. This skill links into both building relationships and working as a team, because actively listening enables you to recall valuable information about individuals and the task at hand (Johnson & Bechler, 1998). Even by merely listening to a colleague’s problems and ideas builds trust and gives a more human aspect to the relationship.

As mentioned earlier, leaders are typically knowledgeable in their fields either by furthering their educational studies or having an effective development programme built within their organisation. Johansson, Fogelberg-Dahm & Wadensten (2010) found that nurses who had more opportunities for evidence-based practice (EBD) had more significant experience in research education and supportive leadership. This indicates that being able to further your educational needs, increases the overall performance of the individual. Although your endeavour to be better in your field of work might be made better by furthering your education, organisations must be aware that specific skills are needed to progress further. To ensure that individuals feel that they are required in the organisation, an effective professional development programme may help in developing effective leaders. Darling-Hammond, Bullmaster & Cobb (1995) also found that a teacher’s ability to lead is connected to teacher learning. Not only does improving the overall teaching of teachers increase the school’s performance, but enables others to develop leadership skills by embedding it in tasks that are not made out to be fake, artificial or formed from a hierarchy.

Although we would typically look at how our organisation can aid us to become effective leaders, we must also seek out the opportunities ourselves and delve a little deeper into our style and skills to become effective leaders.